Partridge or Brown? Why “Stippling” Would Erase the Partridge Silkie

Stop the bait-and-switch: stippling rewrites Partridge by stealth. A response to the ASBC’s new standard proposal for the partridge variety

I’m writing as a breeder with skin in the game. My grandmother, Shiela Buckalew, and I have bred Partridge Silkies continuously since 2012. We started where most people start—figuring it out the hard way. We fixed type first and only then chased color and pattern. We kept the program tight; the only outside blood we ever brought in was from Wendy Watkiss, integrated deliberately to deepen ground color and steady the pattern. The results are public: in 2025 our Partridge line earned two ABA starred wins (confirmed against ABA criteria and pending publication), including Reserve Breed at ASBC Nationals held at the APA National Meet in Fayetteville, Arkansas—and those stars came from two different birds. All of that is to say: true Partridge—rings over red‑bay—is real, workable, and competitive right now. It does not need to be redefined.

Yet that is exactly what the ASBC standards committee is attempting by substituting “stippled” for “pencilled/stenciled” in the Partridge female description. It sounds small. It is not. In the APA Standard of Perfection, those words are not flavor—they are different pattern categories that train judges’ eyes and steer breeders’ selection. Pencilled means organized, curved bands that follow the contour of the feather. Stippled means a fine, diffuse pepper with no ring structure. Partridge Silkies are built on the e^b (brown) base and are defined by rings; Brown Cochin hens (also e^b) are stippled. Swap the word in the Silkie line and you don’t “clarify” what judges see—you change what they reward. And once the judge’s book moves, the gene pool follows. That is how a one‑word edit kills a variety.

Here’s the blunt chain of events. Year one, the book says “stippled,” and comment cards start praising peppered surfaces in the Partridge class. Year two, exhibitors keep what won and cull ringed hens as “off type.” In brown‑base populations this strips Ml (melanotic) from partnership with Pg (pattern); ring architecture collapses to pepper while Mh (mahogany) gets deprioritized because it no longer supports a judged feature. By years three to five most lines are breeding true to a Brown‑type stippled female under a Partridge label. The few breeders still fighting for rings get beaten on the table, lose market pressure to keep the architecture intact, and either drift or give up. Rebuilding once Pg+Ml is allowed to decay is a multi‑year rescue. Change the word and Partridge disappears in practice, no matter how loudly we insist on history.

The committee’s defense of the change boils down to this: on Silkie feather texture, “pencilling shows up as stippling,” especially in the crest and other non‑barbed areas, so the book should say “stippled.” That argument confuses appearance with definition. Silkies are fluffy; barbs don’t lock; edges blur. Everyone knows that. But texture‑induced fragmentation of rings is still fragmentation of rings. The solution is education, not redefinition. The ABA has already issued supplemental judging guidance for Silkies that tells judges exactly how to handle indistinct markings and reduced luster caused by feather structure and even notes that Blue birds lack lacing and should not be penalized for it. In other words, there is already a path that teaches judges to read through Silkie texture without rewriting Partridge as a different pattern.

Now look at what the committee’s examples actually prove. They point to Old English Game duckwing hens—Black Breasted Red and Silver Duckwing—as SOP examples explicitly described as stippled. That only proves where “stippled” belongs; it does not justify importing it into Partridge. The same logic applies to Brown Cochin hens on e^b: they are stippled by definition and remain a different variety. Showing that stipple exists elsewhere doesn’t make Partridge stippled; it shows the categories are distinct and should stay that way. Mahogany deserves its own paragraph because the committee has downplayed it while claiming they will “keep red‑bay.” In U.S. selection, Mh is the difference between a bird that reads Partridge from ten feet and one that fades to confusion. Mh/mh^+ often shows as orange‑gold; Mh/Mh pushes toward brick. Neither dose creates rings—that’s Pg + Ml—but mahogany is what lets the rings be seen. If you erase “pencilled,” the incentive to hold deep ground color disappears with it. That’s another way the one‑word change hollows out the variety: you undercut the canvas that makes the picture visible.

Let’s be just as clear about juvenile plumage, because that gets thrown around to muddle the issue. Partridge juveniles commonly show barring that matures to pencilling at the first adult molt, especially in females. That is normal development, not evidence that “pencilling is impossible” on a Silkie. The pattern is there; the texture makes you work for it in some sections. We don’t rewrite categories because a fluffy bird asks us to look in the right places.

Someone will say, “But judges are already cutting patterned Silkies for indistinct markings and lack of lacing.” That is exactly why the ABA’s standing supplement exists—to tell judges not to penalize texture‑driven indistinctness and to use judgment where lacing is not expressed on Blue. Again: education solves the real problem. Changing the Partridge word does not. It only invites the wrong phenotype to win. So here is the straightforward fix that preserves the breed’s vocabulary and helps judges: keep “pencilled/stenciled” in the Partridge Silkie female description and add a one‑sentence clarifier—Because Silkie feather structure can soften or fragment the rings, the pencilling may appear broken or lightly mottled, especially in the crest and underfluff; selection should still favor discernible pencilling on the back, wing bows, breast, and saddle. That sentence acknowledges reality without redefining identity. Pair it with the ABA’s existing guidance and judge education, and the confusion ends.

If a group genuinely wants to campaign a Brown‑type Silkie with a stippled female surface, there is an honest path: propose a new variety through APA/ABA with the correct vocabulary, representative photos, and whatever qualifying meets the governing bodies require at the time. That protects the Partridge gene architecture and gives exhibitors who prefer the Brown look a legitimate lane. What is not legitimate is to rename Partridge so a different phenotype can win under its banner.

I return to where I started. My grandmother and I have spent nearly fourteen years building Partridge that reads Partridge: rings on e^b, grounded in mahogany, competitive on the table. Many other breeders—some loud, most quiet—have done the same hard work. Change this one word and you will erase that work. You will not “modernize wording”; you will redirect selection, dismantle the Pg+Ml architecture, bleach the ground, and five seasons from now you will be standing in front of a Partridge class that is Brown in fact and “Partridge” only on the coop tag. Withdraw the substitution. Keep “pencilled.” Teach judges how to read it on Silkies. That is how you protect the variety instead of killing it by paperwork. If the word changes, Partridge does not survive. If the word stays and education continues, it does.

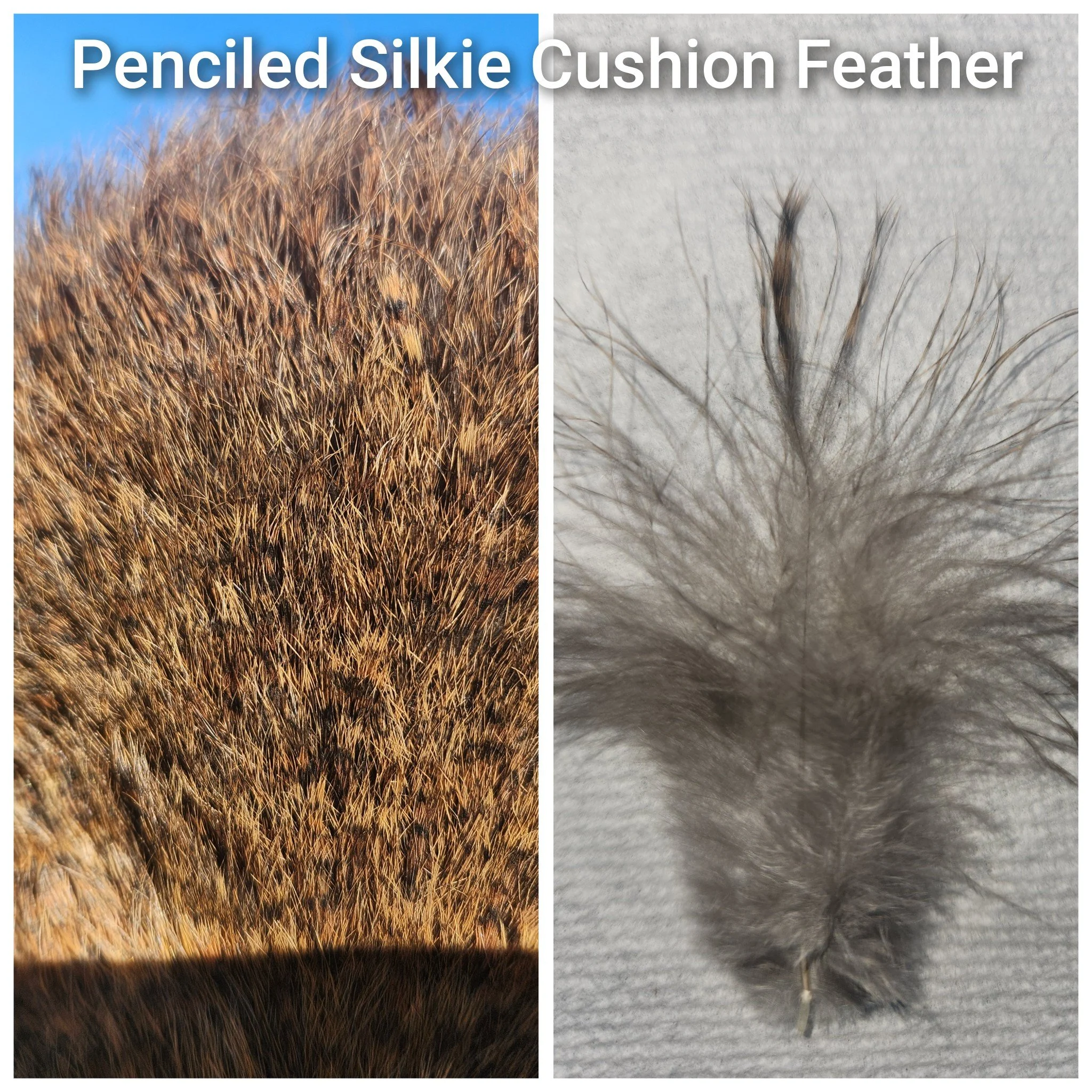

You can see this is penciled/stenciled and not stippled. You can count 3 distinct bands on the right hand photo before the feather shaft shifts to slate undercolor. This feather was taken from the cushion, an area the ASBC standards committee believes it impossible for the penciled/stenciling to appear. If you look at the image on the left, you can see how the non-barbed feathers distort the pattern somewhat ,but if you pay close attention you can see there is distinct bands.

The ASBC (American Silkie Bantam Club) wants us to believe the brown is actually what a partridge silkie is. The fact is Brown is not Partridge. I have attached the direct quote from my messages with the ASBC standards committee chairs below. You will notice a few alarming comments that were made. I am also curious who the long time partridge breeders were on this standards committee. Once again this is a attack on the partridge variety and not just the partridge silkie. Please write the ABA and APA standards committee a letter about these changes.

Quote from ASBC standard chair: "The Partridge silkie was accepted with and incorrect color standard some 60 plus years ago base on a barb feather birds. However the Partridge has been shown same as they are now for that duration. The committee that worked on and agreed on this change were experienced Partridge silkie breeds for many years. We feel this is the best interpretation of what the Partridge silkie should need. They have been breed to the color standard and pattern fors years. I'm not an expert on genetics but if you look there are other breeds that are consider Partridge base with stippling. Read the bb red old English color standard. Also red bay refers to more brown with the Partridge wyandotte carriers. Mahogany should never be a factor in Partridge."

Here is a good example of the 2 differences. The bird on the left is a brown silkie hen from about 7 years ago. The bird on a right is a partridge silkie hen I exhibited earlier this year and took reserve champion featherleg with. You can see the bird on the left has no stenciling/penciling whatsoever, in fact this bird was indeed stippled. The bird on the right however is a true partridge and shows penciling/stenciling. You can the the distinct banding in the photograph.

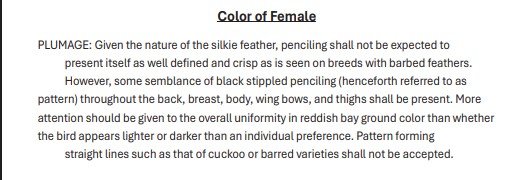

I have found yet another issue with the proposed ASBC (American Silkie Bantam Club) standard change. In the female plumage description of the ASBC's proposed standard change it states "PLUMAGE: Given the nature of the silkie feather, penciling shall not be expected to present itself as well defined and crisp as is seen on breeds with barbed feathers. However, some semblance of black stippled penciling (henceforth referred to as pattern) throughout the back, breast, body, wing bows, and thighs shall be present. More attention should be given to the overall uniformity in reddish bay ground color than whether the bird appears lighter or darker than an individual preference. Pattern forming straight lines such as that of cuckoo or barred varieties shall not be accepted"

Why does it matter that the last line speaks on pattern forming straight lines? It matters because partridge has what is called juvenile plumage that presents as barring or straight lines. It is typically noted the cleaner and crisper the barring the better patterned the partridge. When the standard states this shall not be accepted I would interpret that as a DQ. Why would the ASBC not want us to show our pullets?

Excerpt from the proposed partridge silkie standard. This is from the Summer 2025 ABA Newsletter